Stable moving patterns in the 1-D and 2-D Gray-Scott Reaction-Diffusion System

I presented some of the material from my 2009 paper, and a few of the more interesting videos from the xmorphia exhibit to the Mathematics department at Rutgers University as part of their Fall 2010 series in Mathematical Physics.

Here are the slides in two formats, Powerpoint and Adobe PDF:

Stable moving patterns (Rutgers talk) -- slides (PPS) (13.1 MB)

Stable moving patterns (Rutgers talk) -- slides (PDF) (12.6 MB)

The slides in HTML format are below (scroll down past the five large color images)

The PPS and PDF versions contain extensive graphics and links to the videos I prepared for the talk (which are on YouTube). Some software (e.g. PDF plug-in or a PPS viewer) might not be able to jump to the links directly, but you can cut and paste the URL text (example: "youtube.com/v/kXDTqqgrYCg") into your web browser's address bar. (The same links are also in the slide text below)

In addition to the videos linked from the slides, the participants also saw the videos from the following pages in my main Gray-Scott web exhibit:

k=0.055, F=0.098

(showed briefly while looking for a better example)

k=0.055, F=0.102

(showed briefly while looking for a better example)

k=0.057, F=0.098

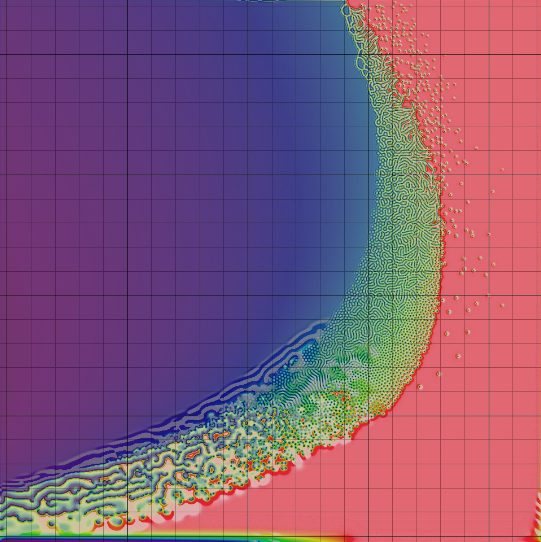

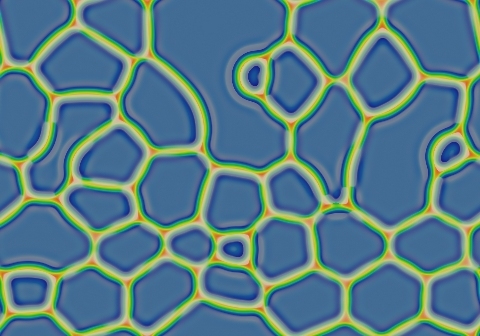

(persistent stripes that form a linked network of polygonal cells,

with gradual evolution into fewer and larger cells reminiscent of soap

bubbles)

k=0.057, F=0.014

(showed briefly while looking for a better example)

k=0.055, F=0.014

(low-U high-V spots that move a bit, then "split" into two spots

which then move and split again, etc.)

What follows is the text of each slide with links to the relevant images and videos. This is intended for readers with a slower connection, or who prefer to go to the YouTube videos directly from the browser without the need to download the slides.

Stable moving patterns in the 1-D and 2-D

Gray-Scott Reaction-Diffusion System

figure: two spots far

figure: U-shaped pattern

figure: 4 spots zigzag

figure: three spots 1-D

figure: five spots

figure: "landspeeder"

Robert Munafo

Rutgers Mathematical Physics Seminar Series

2010 Dec 9, 2 PM — Hill 705

slide 1

Contents (outline of this talk)

- Brief history, motivation and discovery

- Methods and testing

- New patterns and interactions (mostly video)

- Connections; Open questions

- Discussion

slide 2

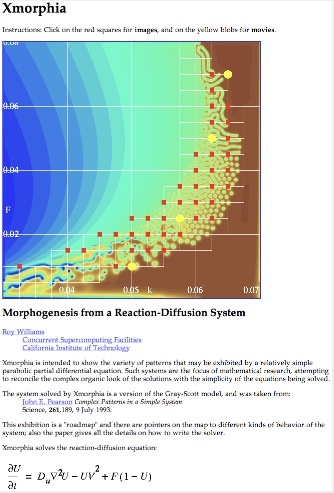

Brief History: Initial Motivation

- 1994: Looking for a problem to run on new hardware

- Supercomputer research led to Williams exhibit at Caltech (shown, left)

- Literature was easy to find; problem was appealing

- Exploring parameter space more closely

figure: 1994 Williams Caltech website

Roy Williams "Xmorphia" web exhibit (Caltech, 1994)

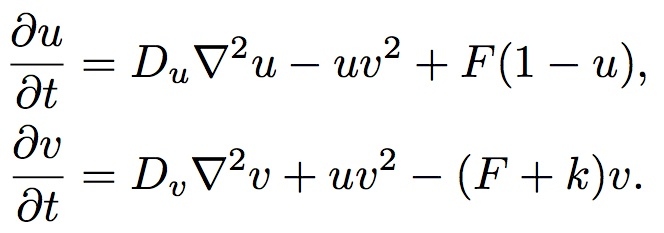

figure: PDE formulas

Pearson "Complex patterns in a simple system" (Science 261 1993) (illust. next slide)

Lee et al. "Experimental observation of self-replicating spots in a reaction-diffusion system" (Nature 369 1994)

(showing part of fig. 1 from Lee et al., and their form of the PDE formulas)

Ferrocyanide-iodate-sulphite reaction in gel reactor

( K4Fe(CN)6.3H2O , NaIO3 , Na2SO3 , H2SO4 , NaOH , bromothymol blue )

slide 3

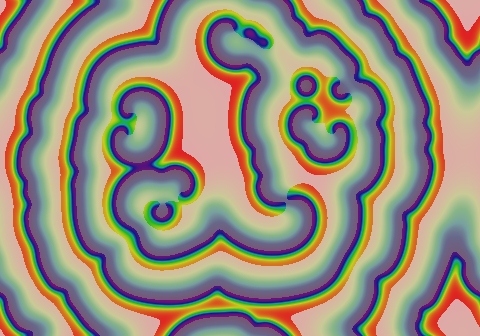

Brief Intro: Parameter Space

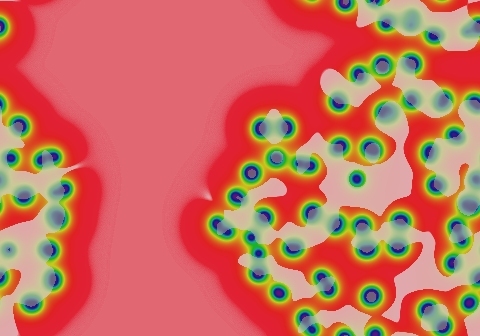

Parameter space and four pattern examples, from Pearson (ibid. 1993)

(showing fig. 3 and part of fig. 2 from Pearson (ibid. 1993))

Coloring imitates bromothymol blue pH indicator as in Lee et al. "Pattern formation by interacting chemical fronts" (Science 261 1993): blue = low U; yellow = intermediate; red = high U

(showing fig. 3 from Miyazawa et al.)

Parameter space visualizations for several reaction- diffusion models, from fig. 3, Miyazawa et al. "Blending of animal colour patterns by hybridization" (Nature Comm. 1(6) 2010)

slide 4

Brief History: 2009 Website Project

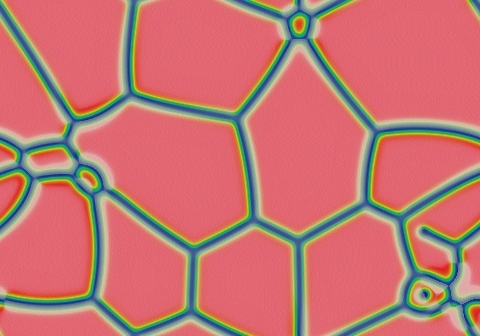

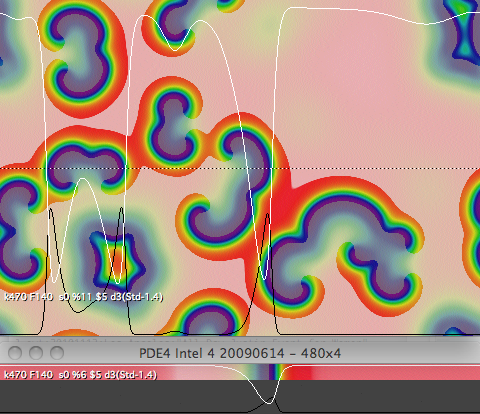

figure 1: parameter map image from my website

- Denser coverage; explore more extreme parameter values

Pearson: 34 sites; 0.045

False color images: purple = lowest U, red = highest U, pastels

= dU/dt > 0

slide 5

New pattern types (2009)

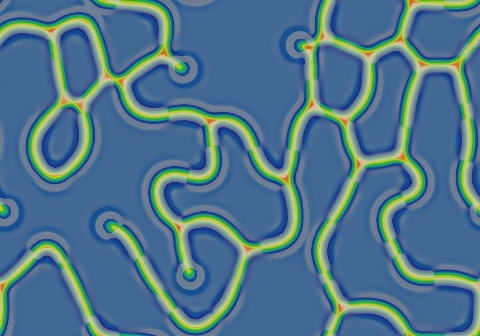

negative soap-bubbles image

k=0.057, F=0.09

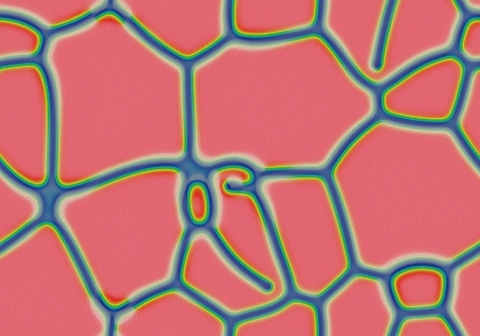

positive soap-bubbles image

k=0.059, F=0.09

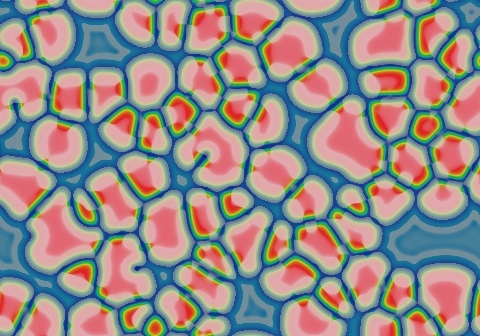

exotic diversity image

k=0.061, F=0.062

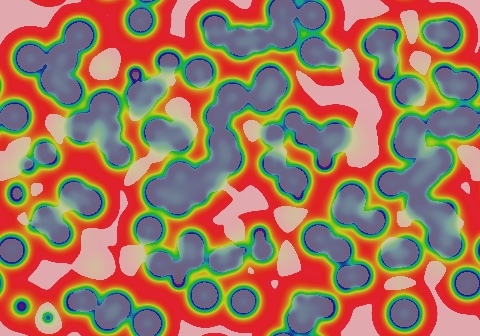

self-sustaining spirals image

k=0.045, F=0.014

(The above 4 images have arrows pointing to a copy of the parameter map image from the previous slide, and showing the locations of the k and F values for each image)

- Some type of exotic behavior at high F values was expected

- Spirals were expected (seen in Belousov-Zhabotinsky and other reaction-diffusion systems)

- k=0.061, F=0.062 has more diversity than all the rest put together

- Also found: mixed spots and stripes; variations in branching; etc.

(Xmorphia parameter map image again)

Munafo (2009) www.mrob.com/pub/comp/xmorphia

slide 6

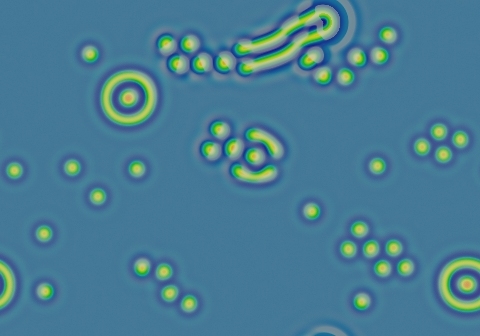

Inherent Instability

Turing-F600-k620.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/kXDTqqgrYCg

k=0.062, F=0.06

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

Each second is 1102 dtu

Initial pattern of low-level random noise (0.4559<U<0.4562; 0.2674<V<0.2676)

Final values: 0.35<U<0.90; 0.00<V<0.36 (approx.)

(Contrast-enhanced images; lighter = higher U)

- At many parameter values, patterns like this grow out of any inhomogeneity, no matter how small

- This is not a consequence of numerical approximation error: proven by mathematical analysis. Dominant wavelength (spot size) depends on reaction dynamics and diffusion rate. Turing "The chemical basis of morphogenesis" (Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London B 237(641) 1952)

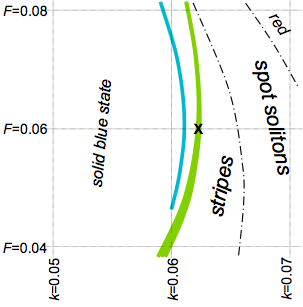

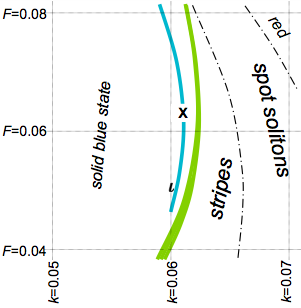

figure: parameter space with Turing and exotic regions

Gray-Scott parameter values for Turing instability (green; width to

scale) and stable moving patterns (blue; width exaggerated). The video

is at X

slide 7

How can we trust these results?

- Arbitrarily low-level noise can generate strong patterns

- Instabilities can exist in the ideal (exact) system, and can be introduced by the numerical method

- Complex patterns are already proven to be real

- These new patterns are far more extraordinary

- Mathematical proof/disproof probably impossible

- How much precision is necessary? Is any finite precision sufficient for proof?

- Is the standard precision "too accurate" to be relevant? The real world has known levels of quantization and randomness: "finite precision"

- Goals:

- Eliminate suspicion of numerical error

- Quantify the sensitivity of these pattern phenomena to precision, randomness, reaction parameters and other environmental conditions

slide 8

Supplement to Slide 8

My diagram illustrating the effects of "precision", "noise" and "randomness" on the robustness of pattern-forming phenomena

^ Q | R L | | ^ | : | : | : | : | M MO:M OM P ---E--------:-----------> | NThis is an abstract (qualitative conceptual) representation of two different types of phenomena that affect pattern-forming systems, viewed as "dimensions" or "parameters" of the laws of physics.

Q represents the amount of quantization that results from the (finite, not infinitesimal) size of atoms. This determines the relative strength of brownian motion and other similar phenomena.

N represents the amount of aberration resulting from numerical methods — roundoff error, the choice of a certain finite grid size to represent a continuous system, etc.

The other letters represent the location of certain pattern-forming systems that have been studied in published work:

P : Pearson (ibid. 1993)

M : Munafo (my various Gray-Scott simulation experiments from 1994 to 2009)

O : Other published Gray-Scott simulations over the period 1994-2009

E : Exact systems (mathematical analysis and proofs)

R : The real world

L : Stochastic simulations, such as certain papers by Prof. Joel Lebowitz of the Rutgers mathematics department.

The vertical dotted line represents one author (Munteanu et al. "Pattern formation in noisy self-replicating spots" Int'l. Jrl. of Bifurcation and Chaos 12(16) 2006) who added various amounts of "Gaussian noise" to a simulation and observed a substantial qualitative change in pattern type (from stripes to spots) as one goes from zero noise up to a level one might expect in real-world experiments, in Gray-Scott simulations with k=0.0655, F=0.05 and all other details as in Pearson (ibid. 1993). I have reproduced these results in my simulations.

Note that these "systems" exist in different types of "reality" : the physical reality of the world around us, the "virtual reality" inside a computer, and the "abstract" existence of mathematical truth. For this and other reasons, there are many more than just two "dimensions" at play and so the chart above is just an illustration of the concept.

I sought to address the general issue of numerical error ("M" systems as compared to "E") and ignoring statistical mechanics ("E" systems as compared to "R").

Verification Examples

figure: two spots (close)

figure: U-shaped pattern

- Two stable moving phenomena

- One is clearly bogus, the other might be real

Two spots maintain the same distance while the pair rotates toward a 45o alignment

U-shaped pattern moves at about 1 dlu per 62,000 dtu (dimensionless units of length, time)

- Define something that is measurable

- Model the sources of error, e.g.:

measured value = true value + simulation error + measurement error

simulation error = f(stability, precision, grid spacing, ...)

CFL (Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy 1928) stability criterion (for the Laplacian term):

C Δx2/Δt

(A higher value means greater stability. Constant C depends on e.g. k and F for the Gray-Scott system)

- Progressively improve the simulation and look for a trend

slide 9

Verification Procedure

screen shot of the same test running in five different-sized grids

- Progressively improve Δx by √2

- Progressively improve CFL stability by √2

- Progressively improve Δt by needed amount (2√2)

| Δx | Δt | Δx2/Δt | pixels(typ.) | |

| "std" | 0.00699 | 0.5 | 9.78×10-5 | 128×128 |

| "s1.4" | 0.00495 | 0.177 | 1.38×10-4 | 180×180 |

| "s2" | 0.00350 | 0.0625 | 1.96×10-4 | 256×256 |

| "s2.8" | 0.00247 | 0.0221 | 2.77×10-4 | 360×360 |

| "s4" | 0.00175 | 0.00781 | 3.91×10-4 | 512×512 |

(amount of calculation increases by 4√2 each time: ratio of 1024 to 1 between "std" and "s4")

Expected Results:

(two-spot pattern): Movement is 100% spurious: measurements should tend towards zero

(U-shaped pattern): If real, velocity should clearly converge on a nonzero value

slide 10

Verification Examples — Results

figure: two spots (close)

Suspect rotating 2-spot phenomenon

cross-qtr. relative model max dU/dt interval velocity std 8.97e-7 5.6e5 1.0 s1.4 4.57e-7 1.12e6 0.50 s2 2.31e-7 2.18e6 0.26 s2.8 1.158e-7 4.34e6 0.129 s4 5.80e-8 8.7e6 0.064

figure: U-shaped pattern

Velocity of U-shaped pattern

model dist pixels time velocity (meas.err) std 0.55418 79.2 35076 1/63294(45) s1.4 0.59863 121.1 37342 1/62379(64) s2 0.57042 163.1 35456 1/62159(27) s2.8 0.56947 230.3 35258 1/61913(44) s4 0.56553 323.5 35009 1/61905(12)Same tests using 4th order Runge-Kutta

model dist pixels time velocity (meas.err) std 0.57937 82.9 36559 1/63101 s1.4 0.56053 113.4 35021 1/62479 same s2 0.56351 161.2 35008 1/62124 as s2.8 0.56517 228.6 35003 1/61934 above s4 0.56574 323.6 35002 1/61870Limits on parameter k (when F=0.06) for stability of U-shaped pattern

model minimum maximum std 0.0608833 0.0609829 s1.4 0.0608796 0.0609831 s2 0.0608777 0.0609831 s2.8 0.0608767 0.0609830 s4 0.0608762 did not test measurement error in all values is +-1 in the last digit- Two-spot pattern movement is bogus

- Moving U-shaped pattern is real; Runge-Kutta gives little if any benefit

- Asymptotic trends in values and in measurement errors, as expected

slide 11

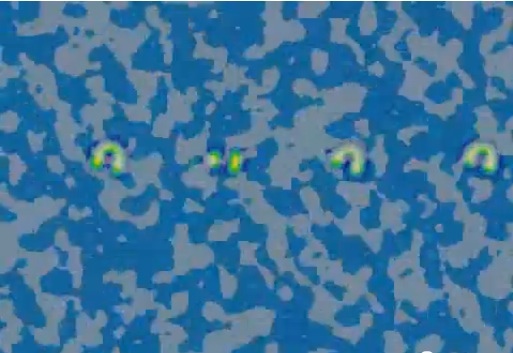

Immunity to Noise

U-noise-immunity.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/_sir7yMLvIo

k=0.0609, F=0.06

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

1 second ≈ 1100 dtu

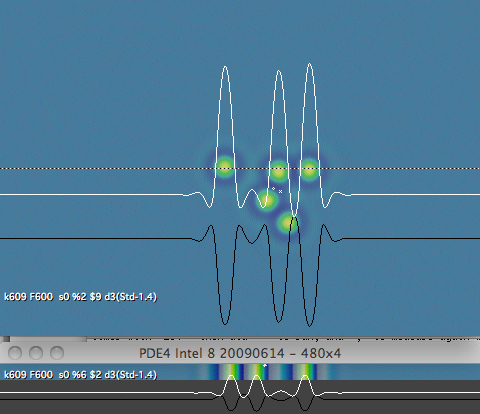

4 U-shaped patterns traveling "up"

Systematic noise perturbation applied once per 73.5 dtu

Amplitude of each noise event starts at 0.001 and doubles every 11,000 dtu (10 seconds in this movie)

At noise level 0.064, three patterns are destroyed; noise amplitude is then diminished to initial level

(False-color: yellow = high U; pastel = positive dU/dt )

- Pattern continues to move in the presence of noise, and generally behaves as expected of a real phenomenon

- Similar tests (e.g. more frequent noise events each of lower amplitude) give similar results

slide 12

Symmetry-based Instability Tests

Daedalus-stability.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/fWfsMVEeP5k

k=0.0609, F=0.06

Periodic boundary conditions; size 2.36w × 1.65h

Manually constructed initial pattern based on parts of naturally-evolved systems

1 second = 265 dtu

Two sets of three noise events; noise event amplitudes are 10-5, 0.001 and 0.1; pattern allowed to recover after each event

Coloring (left image) same as before

Coloring (images below): white = positive dU/dt, black = negative dU/dt, shades of gray when magnitude of dU/dt is less than about 5×10-13

figure: landspeeder (full color)

figure: landspeeder (derivative only)

A pattern with an instability that this test does not help reveal

- Rotating and moving patterns have rotational or bilateral (resp.) symmetry which persists if the pattern is stable.

- Instability and/or a return to symmetry are easier to observe in the derivative

- Test static and linear-moving patterns at different angles to reveal influence by grid effects

- Other tests include shifting parts of a pattern, applying noise to only part of a pattern, etc.

- Such tests can reveal instability more quickly but do not prove stability.

slide 13

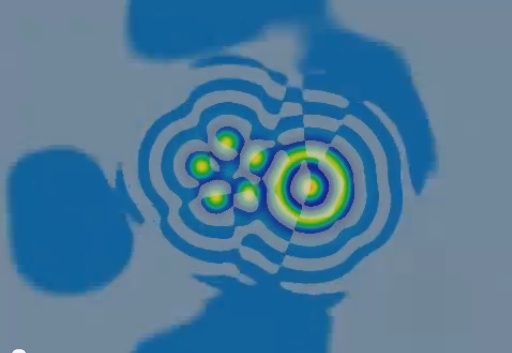

Logarithmic Timebase, Long Duration

- Some phenomena appear asymptotic to stability but actually keep moving forever

- Running a simulation for as long as possible (currently >108 time units) and viewing the results at an exponentially accelerating speed can reveal some of these phenomena

- Repulsion of solitons in 1-D (pictured, lower-right) has been studied mathematically for high ratios DU/DV (Doelman et al. "Slowly modulated two-pulse solutions...", SIAM Jrl. on Appl. Math. 61(3) 2000) with the result: (speed of movement) = Ae-Bt for positive constants A,B

- There are many other phenomena in Gray-Scott systems that slow at similar rates

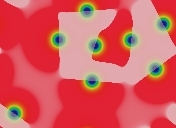

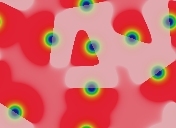

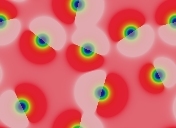

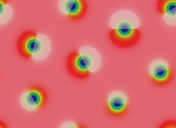

Eight solitons in a 2-D system, k=0.067, F=0.046 :

t=78,125

;

t=1,250,000

;

t=2×107

;

t=3.2×108

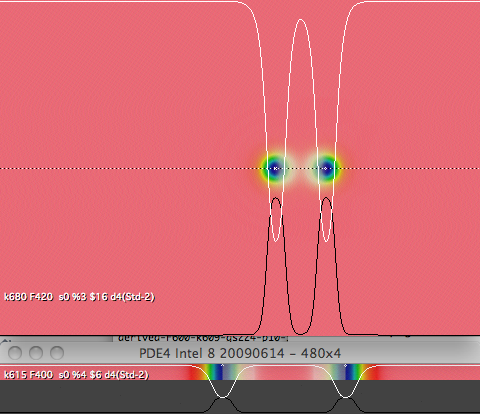

figure 2: pairs of solitons in 2-D and 1-D

(larger, upper part of figure) Pair of solitons in 2-D system,

k=0.068, F=0.042

(smaller, lower part of figure) Pair of

solitons in 1-D system, k=0.0615, F=0.04

slide 14

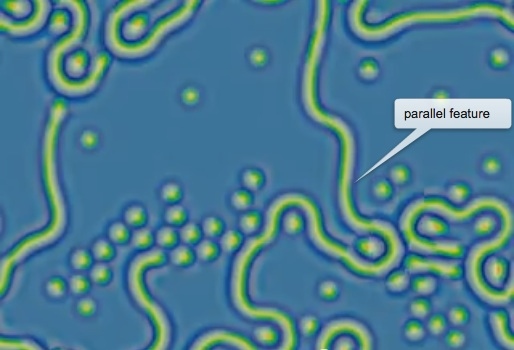

Discovery - Great Diversity

Original-F620-k610-fr159.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/wFtXwFfrwWk

k=0.061, F=0.062

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

1 second ≈ 1190 dtu

Initial pattern of a few randomly placed spots of relatively high U on a "blue" background (secondary homogeneous state, approx. U=0.420, V=0.293)

(False-color: yellow = high U; pastel = positive dU/dt )

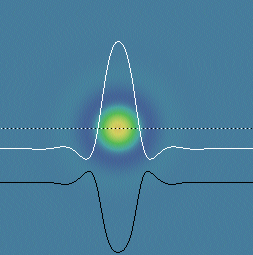

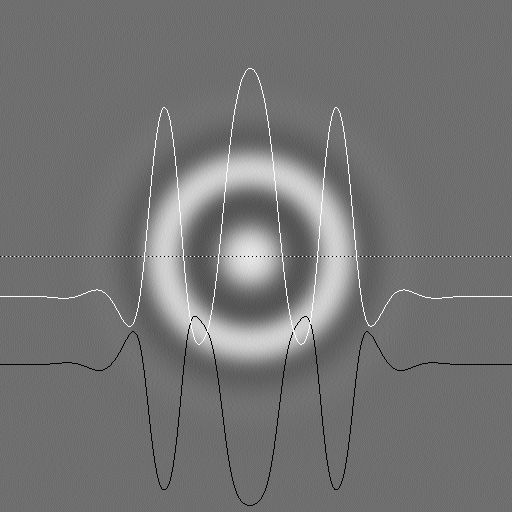

figure 1: normal soliton

Ordinary spot soliton (k=0.067, F=0.062)

figure 2: negative soliton

"negative soliton" (k=0.061, F=0.062)

In figures 1 and 2: White curve = U; Black curve = V; dotted line shows cross-section taken

- Part of routine scan for website exhibit project

- "Negative solitons" (hereafter called "negatons") exhibit attraction and multi-spot binding

- Several types of patterns in one system

- The "target" pattern is not stable at these parameter values, but is stable at the nearby parameters k=0.0609, F=0.06

("iota" image from figure 2 in Pearson (ibid. 1993))

"negative solitons" in Pearson (ibid. 1993)

"Pattern ι is time independent and was observed for only a single parameter value."

(parameters unpublished, probably k=0.06, F=0.05)

slide 15

Discovery - Moving U Pattern

U-discovery-F620-k609-fr521.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/xGMuuPYhLiQ

Original coloring — youtube.com/v/ypYFUGiR51c

k=0.0609, F=0.062

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

1 second ≈ 3900 dtu

Initial pattern and coloring same as before

figure: parameter space with ι and X

This video is at X; Pearson's type ι is shown

- Moving "U" visible to right of center, short-lived (hits two negatons)

- More unexpected negaton behavior: being "dragged" by other features

slide 16

Long Duration Test

Different Behaviors at Multiple Time Scales

Exponential-time-lapse.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/-k98XOu7pC8

k=0.0609, F=0.062

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

Initial pattern of spots (randomly chosen U<1, V>0) on solid red (U=1, V=0) background; coloring same as before

Video uses accelerating time-lapse: simulation speed doubles every 6.7 seconds

- First 30,000 dtu (40 seconds into video): blue spots grow to fill the space (a very common Gray-Scott behavior)

- Up to 1.25 million dtu (75 seconds into video): complex behavior, double-spaced stripes, solitary negatons, etc. until all empty space is filled

- Up to 6 million dtu (90 seconds into video): chaotic oscillation of parallel stripes growing, shrinking and twisting; gradually producing more spots

- Sudden onset of stability: All chaotic motion ends (whole system drifts very slowly)

slide 17

Complex Interactions

complex-interactions-1.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/hgTBOf7gg8E

k=0.0609, F=0.06

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

Each second is 10,000 dtu

Manually constructed initial pattern based on parts of naturally-evolved systems

Coloring same as before

- U-shape can influence other objects and survive (although it generally does not)

- The clusters of negatons along the top move and rotate, very slowly

slide 18

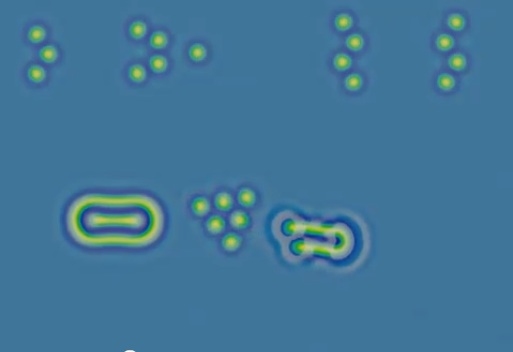

Slow Movement, Rotation

slow movers and rotaters.mp4 — watch (YouTube)

— youtube.com/v/PB3lPMhwIo0

k=0.0609, F=0.06

Periodic boundary conditions; size 3.35w × 2.33h

Each second is 100,000 dtu

Manually constructed initial pattern based on parts of naturally-evolved systems

Coloring same as before

- There are many very slow patterns; a few of the more common are shown here

- The "target" (negaton with annulus) is a common product of spotlike initial patterns, and adjacent negatons typically make it move or rotate

- The 4 negatons left by the collision of two U patterns are in an unstable equilibrium

figure 1: rotating "target with 9 spots" undergoing tests

Stability analysis of another slow-rotating pattern

figure 2: 4-spot pattern undergoing tests

Stability testing of 4-negaton pattern; stable form shown at right

slide 19

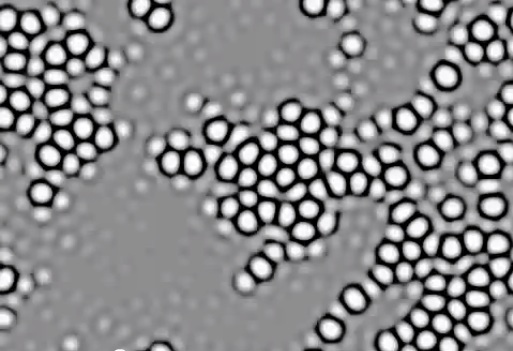

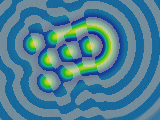

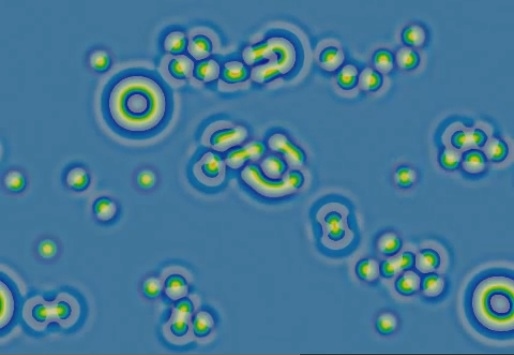

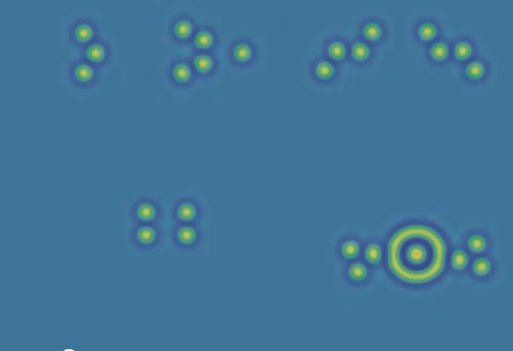

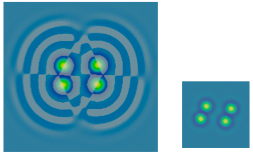

A Gray-Scott Pattern Bestiary

figure: a large collection of patterns

k=0.0609, F=0.06 Contrast-enhanced grayscale, lighter = higher U

Most patterns were manually constructed from parts of naturally occurring forms

Note: Many of these are not yet thoroughly tested

- Almost everything that keeps its shape moves indefinitely. In general, a pattern will:

- move in a straight line, if is has (only) bilateral symmetry

- rotate, if it has (only) rotational symmetry

- move on a curved path, if it has no symmetry at all

- Lone negatons are frequently "captured" and/or "pushed" by a moving pattern

slide 20

Relation to Other Work:

"Negaton" Clusters and Targets

- Spots and "target" patterns very similar to the Gray-Scott "negatons" are seen in papers by Schenk, Purwins, et al.

- In a 1998 work, a 2-component R-D system is studied; the spots are stationary and are reported to "bind" into stable groupings with specific geometrical configurations (as shown). There are differences between this system and Gray-Scott, evident in which "molecules" are reported as stable.

- In a 1999 work (by Schenk alone) a 3- component R-D system includes a "target" pattern with a very similar cross- section.

(Showing parts of fig. 1 and fig. 5 from Schenk et al. (1998))

From Schenk et al. "Interaction of self-organized quasiparticles..." (Physical Review E 57(6) 1998), fig. 1 and 5 The pattern marked * (subfigure "b") is stable in Gray-Scott at {k=0.0609, F=0.06}, the pattern marked × (subfigure "e") is not.

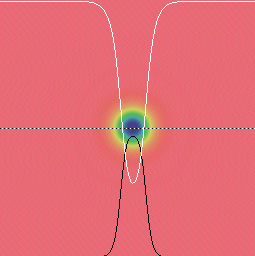

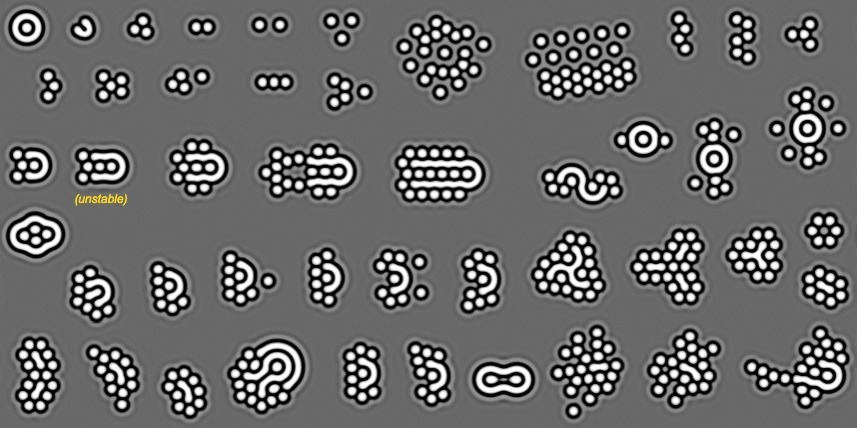

figure: target pattern

Target pattern in Gray-Scott, k=0.0609, F=0.06, with U and V

levels at cross-section through center

(Showing part of fig. 4.37 from Schenk PhD dissertation)

Target pattern from C. P. Schenk (PhD dissertation, WWU Münster, 1999) p. 116 fig. 4.37

slide 21

Relation to Other Work: Halos

- The light and dark "rings" or "halos" are seen in physical experiments and numerical simulations intended to model both physical and biological systems

- When spots appear in these systems, as in Gray-Scott, the spots tend to be seen at certain "quantized" distances

- Halo amplitudes, spot spacings and relative sizes differ; this also reflects changes seen in Gray-Scott as the k and/or F parameters are changed

figure: two "negatons" at stable weakly-bound distance

Negatons with halos (Gray-Scott system, k=0.0609, F=0.06, lighter = higher U; exaggerated contrast)

(showing fig. 11 from Barrio et al. 2009)

Spots with halos in numerical simulation by Barrio et al. "Modeling the skin patterns of fishes" (Physical Review E 79 031908 2009) fig. 11

(showing fig. 3d from Stollenwerk web page)

Spots with halos in gas-discharge experiment by Lars Stollenwerk ("Pattern formation in AC gas discharge systems", website of the Institute of Applied Physics, WWU Münster, 2008) fig. 3d

Halos also appear in models by Schenk, Purwins, et al (ibid., 1998 and 1999, shown on previous slide) in work related to gas discharge experiments

slide 22

One-Dimensional Gray-Scott Model

- There are extensive results on the 1-D system based on rigorous mathematical analysis (most are for higher ratios DU/DV than in the systems presented here)

- The "spiral wavefront" observed at many parameter values in the 2-D system is also a viable self- sustaining stable moving pattern in the 1-D system at the same parameter values

- For many parameter values that support "negative stripes" in the 2-D system, certain asymmetrical clumps of "negatons" form stable moving patterns in the 1-D system

- Negatons in 1-D were reported (shown) as early as 1996

(showing fig. 9 from Mazin et al. 1996)

Single 1-D negaton inside a growing region of solid "blue state" at k=0.06, F=0.05, from Mazin et al. "Pattern formation in the bistable Gray-Scott model" (Math. and Comp. in Simulation 40 1996) fig. 9

figure 1: spiral and fast pulse

2-D spirals and 1-D pulse at k=0.047, F=0.014

figure 2: two slow-moving patterns

Representative 2-D and 1-D patterns at k=0.0609, F=0.06

(Note: Non-existence results of Doelman, Kaper and Zegeling (1997) and of Muratov and Osipov (2000) are not applicable because they concern models with a much higher ratio DU/DV )

slide 23

Open Questions

- Why does the U-shaped pattern move and keep its shape?

— As parameter k is increased, leading end of double-stripe (shown) moves faster, but trailing end moves slower and the object lengthens; in the other direction (decreasing k) the reverse is true

— When these two speeds are closely matched, the U shape (shown) neither grows nor shrinks — why?

- Do these patterns appear in other reaction-diffusion models?

— Universal presence of other pattern types suggests this; parameter space maps should make it easy to find; nearby Turing effect is possibly relevant

- Can any of the special properties of these patterns be proven mathematically?

— 1-D systems seem particularly well suited to this task

— Shape of negaton "halos" is easy to solve

— Most existing work applies conditions or limits that exclude the commonly studied DU/DV=2 systems

slide 24

Discussion

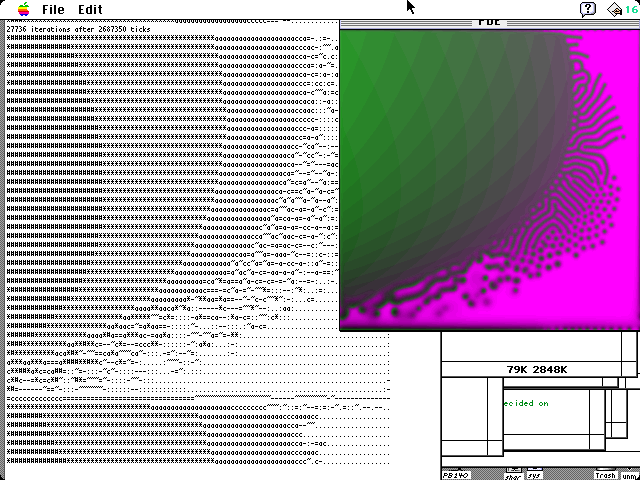

screen image of my Gray-Scott program in July 1994

18 MFLOPs/sec. Note ASCII text rendering of pattern

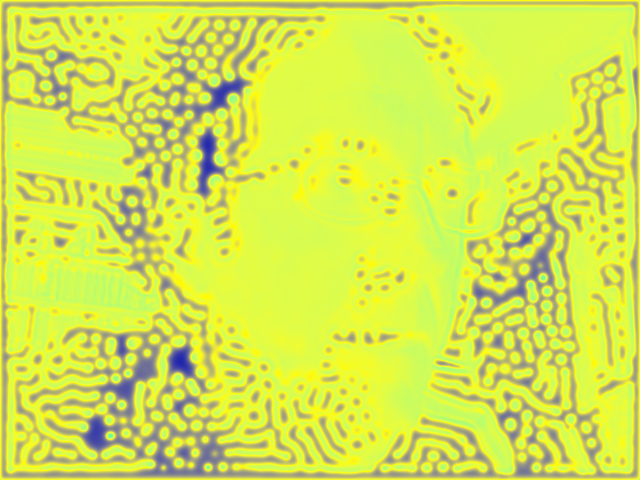

my Gray-Scott video screensaver, September 2010

(depicts a Gray-Scott image using a brightness map of my face to

control parameter k)

Robert Munafo mrob.com/sci

(email: click "contact" below)

(the background of this slide is a detailed parameter map image generated in 2004, showing k from 0.0582 to 0.0682 and F from 0.031 to 0.051, in a color scheme that depicts low U values as blue and high U values as yellow.)

slide 25

This page was written in the "embarrassingly readable" markup language RHTF, and was last updated on 2014 Dec 03.

s.27

s.27